BP and the Bankers

Question of the Day: What do the oil catastrophe and the Wall Street collapse have in common?

By Robert Kuttner – Co-founder & co editor of American Prospect

By Robert Kuttner – Co-founder & co editor of American Prospect

Three big things, I’d say.

In both cases, a powerful, politically protected industry invented something that could not easily be repaired when it broke. We seem to be entering an age when complex technologies, whether financial or physical, sometimes literally have no solutions when they go haywire in unanticipated ways. We thought this might happen with nuclear power (and it still could); but for now deepwater drilling is the bigger menace.

Secondly, in both cases the proverbial ounce of prevention was not applied. Had existing laws been enforced, and had the political process not corrupted the regulatory process, these man-made calamities didn’t need to happen. In the case of the oil disaster, which is fast becoming the worst single environmental catastrophe ever, America’s long-term failure to move away from dependence on carbon fuels combined with pure short-run political capture. By now, we should have been at the point of energy conversion where high risk, mile-deep undersea wells were not used at all. But even so, this blowout would have been averted had existing laws been enforced.

It’s the same story with the financial collapse. We didn’t need these exotic, doomsday financial instruments. And had the regulators not been in bed with the industry, the crisis would have been headed off at any of several earlier stages. But the worst common element is this: both crises are teachable moments that our president could be using to transform public opinion. Yet despite these gifts from the progressive gods, President Obama seems congenitally unable to rise to the occasion.

It appeared, in the end game of the health reform effort and at moments in the financial reform fight, that we were seeing sparks of the Obama whom we so admired on the campaign trail. But Obama’s performance in the oil disaster seems a case of one step forward, two steps backward.

If ever there were a moment to make clear that our energy future cannot be left to the energy industry, and to rally the public on behalf of a long term shift away from carbon fuels to renewable sources, it is now. Will we ever have a better, more graphic villain than BP? Will we ever have the public more on our side? Will we ever have Republicans with dirtier hands?

In the late sixties and early 1970s, the environmental movement burst on the national stage because the environmental assaults of that era were immediate and undeniable — from oil spills to smog to the Cuyahoga River catching fire. Thanks to the victories of that era, environmental damage has become less palpable and pyrotechnic.

Global climate change, the ultimate menace, is gradual, insidious, ineluctable, contested, and seldom vividly symbolized. By contrast the BP blowout is immediate, tangible, and terrifying. Even the Limbaughs and the Becks cannot deny what is dominating TV week after week, and the right is making a fool of itself by lurching from attacking the president’s daughter to blurting out that “accidents happen.”

There is more than a germ of truth, however, in the right’s argument that Obama was slow off the mark to get on top of this crisis, just as he was pitifully slow to clean house at the Minerals Management Service he inherited from Bush. And if the administration does not pick up its game, the Tea Party right will make the Gulf catastrophe Obama’s fault, just as it has made the slow pace of recovery and the bank bailouts Obama’s fault.

I have been in a number of conversations, as a journalist, a public lecturer, privately, and as author of the new book A Presidency in Peril, in which Obama loyalists urge me to cut the president a little more slack. It’s only sixteen months into his presidency. He is still learning. He did, after all, deliver health insurance reform. In that battle, with two outs in the ninth inning, he discovered his inner partisan and fought for a Democrats-only bill, and prevailed.

And he is about to deliver financial reform, right?

But in both cases, the credit goes more to legislative leaders who would not let the bills die and to progressive lobby groups such as H-CAN and Americans for Financial Reform. There is still a furious fight over key provisions in the House and Senate reform bills, and in many cases Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner is weighing in on behalf of weaker rather than stronger measures.

With the spotlight off legislative floor action, and a lot of the deals being made in backrooms, the financial industry hopes to gain back ground that it lost as public opinion shifted in favor of tougher reform measures.

The financial reform battle is an epic David-Goliath contest. The banking lobby spends more in a day than Americans for Financial Reform’s annual budget. The leadership of AFR combined with the actions of courageous senators such as Maria Cantwell, Jeff Merkley, Al Franken, and a couple of dozen others, shows how public opinion could be rallied.

But imagine how much more reform we could get if the President of the United States clearly weighed in on behalf of David rather than Goliath.

This could also be a defining moment in the fight for a clean energy future if President Obama used it as such.

Time is running out for this president to lead. If he continues temporizing rather than leading, the moment passes, and the Republicans pick up substantial numbers of seats in Congress. The window closes, both for transformative progressive reform and for a successful Obama presidency. Even worse, the initiative passes to a truly lunatic rightwing.

I would say to the loyalists: Yes, this president faces multiple challenges that are really hard, as well as a fiercely obstructionist Republican Party and a grass-roots right in league with a media machine. But all crisis-presidents faced obstacles and the great ones turned them to opportunities.

The other day, one of the president’s enthusiasts told me that Obama has been very successful in terms of the agenda that he set out to achieve. Sorry, but that doesn’t cut it. A president has to play the hand history dealt him.

Robert Kuttner’s latest book is A Presidency in Peril. He is co-editor of The American Prospect and a senior fellow at Demos.

________________

Was the Gulf Oil Disaster a Result of a BP Big Whig Party?

Submitted by louise hartmann

The Times-Picayune reported that an oil worker who survived the April 20 explosion of the Deepwater Horizon, that killed 11 people and started a disastrous oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico, said a key safety measure was not being implented on the rig.

Lawyer Scott Bickford said his client claims a column of mud was being removed from an exploratory well before it was sealed with a top cement cap — a move he described as “human error” that may have in turn failed to prevent the deadly explosion.

A statement from cement contractor Halliburton, reported by the New Orleans newspaper, confirmed the top cap was not installed. The column of heavy mud is one of the core defenses relied upon by drillers to prevent explosions.

So they cut corners to get the job done quickly. Here’s a question. Have you ever worked in a place where the bigwhigs were coming to town and you had to quickly get everything ready for them?

Remember that there were six senior British Petroleum executives on the oil rig at the time of the explosion, celebrating a recent safety award the company had gotten. Getting senior executives out to an oil rig all at the same time is something that requires some coordinating and planning.

What if the drillers and Halliburton were told that the executives were going to be there on April 20th for the party, and therefore they had to hurry to get the job done? And therefore they skipped the time-consuming step of putting the mud plug in and went straight to the cementing process, apparently the fatal mistake that let the giant methane bubble rush up and explode the rig?

Was this entire disaster the result of a hurry-hurry-up because the big shots were flying out by helicopter and the riggers had to get things done “stat”? Who were these six executives? How far out was their visit planned?

Did Halliburton and Transocean cut corners because they were either explicitly told to by BP or implicitly pressured to by BP because the executives were on their way out for the party?

And why is nobody talking about who these executives were, and nobody is telling the life and family stories of the eleven workers who died in the rig explosion?

Inquiring minds want to know.

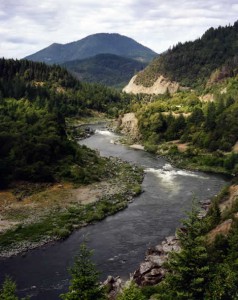

Rough Water

The Likely Removal of Four Dams on the Klamath River Will Mark the Largest Dam Decommissioning in History. An Unlikely Alliance of Farmers, Fishermen, Ranchers, and Indians Made It Happen.

By Jacques Leslie

photo courtesy Robert Dawson, www.robertdawson.com

Maybe the Klamath River basin would have turned itself around without Jeff Mitchell. Back in 2001, at the pinnacle of the conflict over the river’s fate, when the Klamath earned its reputation as the most contentious river basin in the country, Mitchell planted a seed. Thanks to a drought and a resulting Interior Department decision to protect the river’s endangered fish stocks, delivery of Klamath water to California and Oregon farmers was cut off mid-season, and they were livid. They blamed the Endangered Species Act, the federal government that enforced it, and the basin’s salmon-centric Indians who considered irrigation a death sentence for their cultures. The basin divided up, farmers and ranchers on one side, Indians and commercial fishermen on the other. They sued one another, denounced one another in the press, and hired lobbyists to pass legislation undermining one another. Drunken goose-hunters discharged shotguns over the heads of Indians and shot up storefronts in the largely tribal town of Chiloquin, Oregon. An alcohol-fueled argument over water there prompted a white boy to kick in the head of a young Indian, killing him.

Mitchell sports two long black braids that instantly establish his identity as a Native American – in fact, he’s a leader of the three-tribe confederation known as the Klamath Tribes of Oregon. In the midst of the conflagration, when Indians weren’t exactly a welcome sight in farming territory, Mitchell knocked on farmers’ doors to express his condolences for their waterless plight. His intent was to “help the farmers to understand that the tribes weren’t going to leave them isolated through this ordeal,” and to explain that he could sympathize because his tribe had endured comparable trials. On his way to a conversation with approachable farmers in the back of a restaurant, he had to walk through the main dining room, filled with less hospitable farmers who’d been idled by the water cut-off. “Everybody just stopped and stared at me, and some of those stares were pretty icy,” Mitchell says. “That was one of the toughest things I’ve ever done.” If his gesture registered, the evidence at the time was scant – most farmers thought reconciliation with Indians was an unimaginable, even subversive idea.

It’s possible, too, that the Klamath basin would have arrived at an agreement to restore the river without Becky Hyde. Distressed by the Klamath system’s drastic environmental decline, she and her husband Taylor moved their cattle ranch in 2003 to a badly eroded, thoroughly overgrazed parcel of stubble straddling the Sycan River, a Klamath tributary. If restoration could be done here, it could be done anywhere, they figured, and immediately set to the task. Like virtually all the basin’s other residents, the Hydes are not wealthy, and the production constraints they placed on the land to promote its health – including cutting their herd to a fraction of its former size – dramatically reduced their ranch’s potential income. They also designed a conservation easement that obligated future owners to continue promoting the land’s recovery; then, stunningly, they turned over trusteeship of the property to the Klamath Tribes of Oregon, effectively sharing the land’s stewardship with the Native Americans who’d once lived on it. Like the farmers, most Klamath ranchers chiefly viewed Indians as threats to their water supply, and the Hydes’ act leapt across the Indian/rancher chasm. One of Becky’s rewards was a death threat.

A farmer repesentative said: “My friends are my enemies and my enemies are my friends.”

Maybe the agreement announced in January to take down four dams on the Klamath, opening the way for river restoration, would have happened without Troy Fletcher, or Steve Kandra, or Greg Addington. Fletcher, a leader of the Yurok tribe, was notorious among farmers for his vitriolic denunciations of them, but at a meeting of basin leaders in 2005, he suggested that both sides stop attacking each other in the media – and, surprisingly, the farmers agreed. That led to an end of public recrimination and the beginning of trust-building. Kandra, a farmer who filed a lawsuit against the US Bureau of Reclamation over the 2001 water cutoff, turned around a few years later and worked toward reconciliation with the tribes, provoking outrage from fellow farmers. Addington, who heads the farmers’ association, endured fierce criticism for his conciliatory negotiating stance. Basin allegiances became so jumbled, he said, “My friends are my enemies, and my enemies are my friends.”

None of these courageous acts was indispensable, but together their impact was incalculable: At a time when cooperation among basin inhabitants seemed far-fetched, they introduced the idea that reason and compassion could overcome hatred. It’s now clear that Mitchell, the Hydes, Fletcher, Addington, Kandra are pathfinders whose concern for the watershed’s well-being has opened the way for the world’s biggest dam removal project, the key component of one of the world’s largest and least likely river restoration plans. Only a few years ago, the Klamath embodied the failure of legal and political systems to resolve natural resources disputes; now, it stands as an example of how to step past confrontation and negotiate. The agreement united farmers, tribespeople, commercial fishermen, electric utilities, even Warren Buffett and George W. Bush. Back in 2002, a comprehensive deal on river restoration was a long shot. Today it’s a fact, and dam removal, though not certain, stands a better-than-even chance of taking place. If it does, the effort to revive the river and its gravely depleted salmon runs would comprise what Steve Thompson, the US Fish and Wildlife Service representative in negotiations with the utility that owns the Klamath dams, has called “one of the most amazing restoration projects in the world.”

Says Patrick McCully, executive director of the Berkeley, California-based anti-dam nonprofit International Rivers, “To see that dams of such size can be brought down, that these concrete monuments that people view as permanent parts of the landscape can be temporary parts of the landscape – I think that is hugely significant.” The prototypical river starts in high mountains, descends quickly through canyons, then spreads out across marshes at its mouth. By that standard, the Klamath River is geographically backward, for it originates in the high, flat Oregon desert and negotiates steep, picturesque canyons near its mouth in California. Though its length is modest – a mere 254 miles, a tenth of the Mississippi’s – it once contained the Pacific Coast’s third most productive salmon fishery, trailing only the salmon runs on the Columbia and Sacramento Rivers. Remoteness is the Klamath’s burden and its saving grace: Thanks to a constantly shifting sand bar at its Pacific Ocean mouth, it is largely unnavigable and, probably as a result, no big city or industry occupies its shores.

For most of the last 1,500 years, the river supported a sustainable salmon economy. Salmon were at the heart of all the Klamath’s tribal cultures, and Indians were careful not to over-harvest them. Each summer, the lower Klamath’s Yurok and Hoopa tribes blocked the upstream paths of spawning salmon with barriers; then, after ten days of fishing, they removed the barriers, allowing upstream tribes to take their share. As the salmon completed their lifecycle, dying in the waters where they’d been spawned, they enriched the watershed with nutrients ingested during years in the ocean. Among the beneficiaries were at least 22 species of mammals and birds that eat salmon. Even the salmon carcasses that bears left behind on the riverbanks fertilized trees that provided shade along the river’s banks, cooling its waters so that the next generation of vulnerable juvenile salmon could survive.

“We tried to go to court, to go through the political process, but it didn’t work. …The big issues were still out there, and we still had to resolve them.”Salmon’s biological family may have started in the age of dinosaurs a hundred million years ago. They’ve survived through heat waves and droughts, in rivers of varying flow, temperature, and nutrient load – but they were as ill-prepared for Europeans’ arrival as the Indians themselves. Gold miners who showed up in the mid-nineteenth century washed entire hillsides into the river with high-pressure hoses and scoured the river’s bed with dredges. Loggers dragged trees down streambeds, causing massive erosion, and dumped sawdust into the river, smothering incubating salmon eggs. Cattle grazed at the river’s edge, causing soil erosion and destroying shade-giving vegetation. Farmers diverted water to feed their crops.

The dams were the crowning blows. Between 1908 and 1962, six dams were built on the Klamath. The tallest, the 173-foot-high Iron Gate, is the farthest downstream, and definitively blocked salmon from the river’s upper quarter – after it was built, the river’s salmon population plummeted. In addition, the dams devastated water quality by promoting thick growths of toxic algae in the reservoirs. For Klamath basin farmers, however, the dams were deemed indispensable, as they generated hydropower that made pumping of their irrigation water possible.To the farmers, the potential loss of the dams’ hydropower was considered no less crippling than an end to Klamath-supplied irrigation.

About a third of the farmers in the area are descendants of World War I and II veterans who won national drawings for Bureau of Reclamation “Klamath Project” homesteads on drained wetlands; others simply responded to the Bureau’s invitations to settle the 350-square-mile expanse of land spread across south-central Oregon and northeastern California. As Addington, executive director of the Klamath Water Users Association, puts it, “People showed up from New Jersey, having won a homestead, and went ‘Holy cow, what did I just get myself into?’”

In addition to eking a living from the fields, the farmers built homes, schools, churches, whole towns. Even now, the sort of large-scale corporate farming that reigns in California’s Central Valley is unknown in the basin. Farms are modest, family owned, and generate incomes estimated at less than $15,000 a year. Not unreasonably, the farmers assumed that in return for turning swamps into productive acreage, they were owed cheap water and power in perpetuity.

For most of the last century, the farmers were oblivious to the damage that dams and water diversions caused downstream, while the tribes and commercial fishermen quietly seethed. The annual salmon run, once so abundant that people caught fish with their hands, was roughly pegged at more than a million fish at its peak; in recent years it has dropped to perhaps 200,000 in good years, and as low as 12,000 – below the minimum believed necessary to sustain the runs – in bad years. Spring Chinook, which once comprised the river’s dominant salmon run, entirely disappeared. Two fish species – the Lost River sucker and the shortnose sucker – that once supported a commercial fishery, were listed as endangered in 1988. Coho salmon were listed as threatened nine years later.

Read the full article:Rough Water

More Insight